Published in Manila Today

The play written by Chris Millado and directed by Andoy Ranay was originally staged in 1985 by the Philippine Educational Theater Association (PETA) at the height of political unrest brought about by the years of dictatorship since 1972 and then intensified by the killing of Ninoy Aquino in 1983. A year after the play’s staging, the Marcos dictatorship will be toppled down by the people’s uprising known as the People Power. The stories, although completely different in settings and characters, are weaved by a common cause symbolized by an unseen person whose encounters are mentioned in passing by the characters in each act.

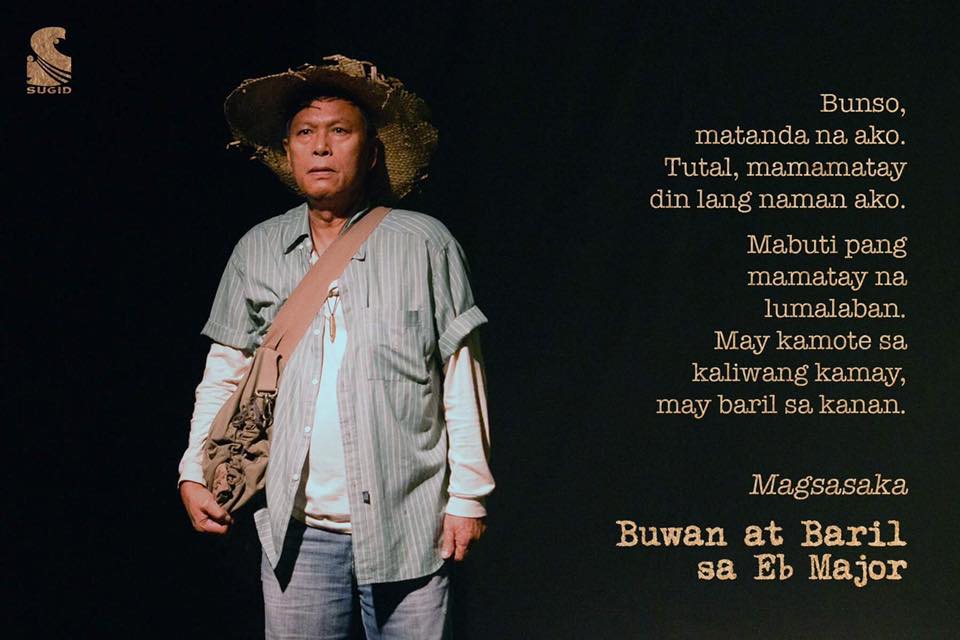

The opening act is a reunion of siblings Manggagawa (Danny Mandia) and Magsasaka (Crispin Pineda) during the 1984 Lakbayan. The siblings who have not seen each other for a decade shared their experiences and struggles in the countryside and in the factories in the cities. The farmer and worker dialogue is the perfect opening act as it will also open the realities of the majority of the Filipino people that they experience until now.

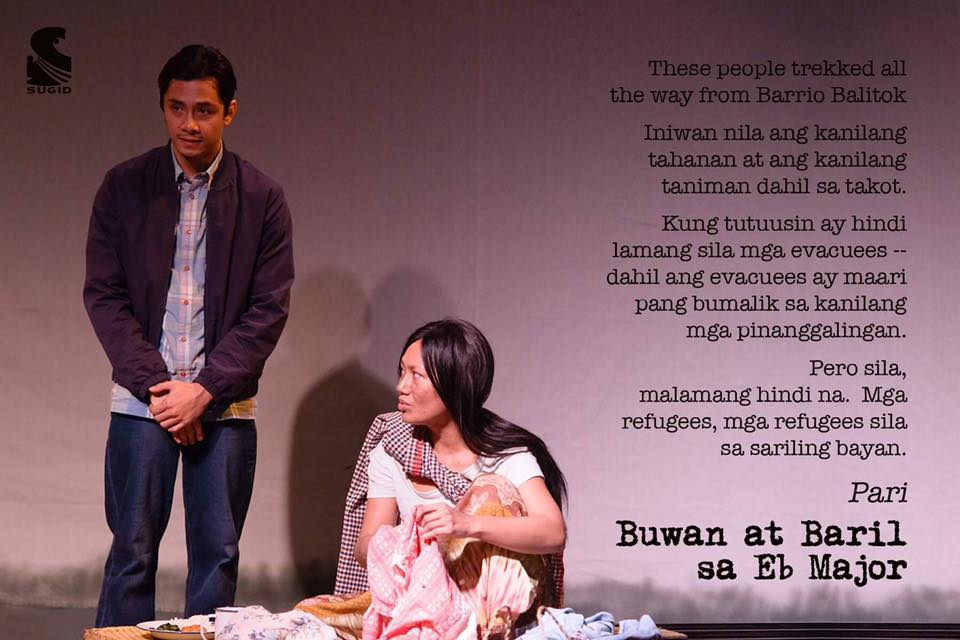

A highly emotional scene of the Pari (JC Santos) and Babaeng Itawis refugee (Angeli Bayani) left the audiences sniffling. The Itawis woman narrated the killing of her father and the Priest shared his personal reasons for helping the refugees. At the end of the scene, Bayani delivered her monologue in the language of her character that the audiences cannot understand, no more translations, but performed it too real and heartbreakingly that words were no longer needed.

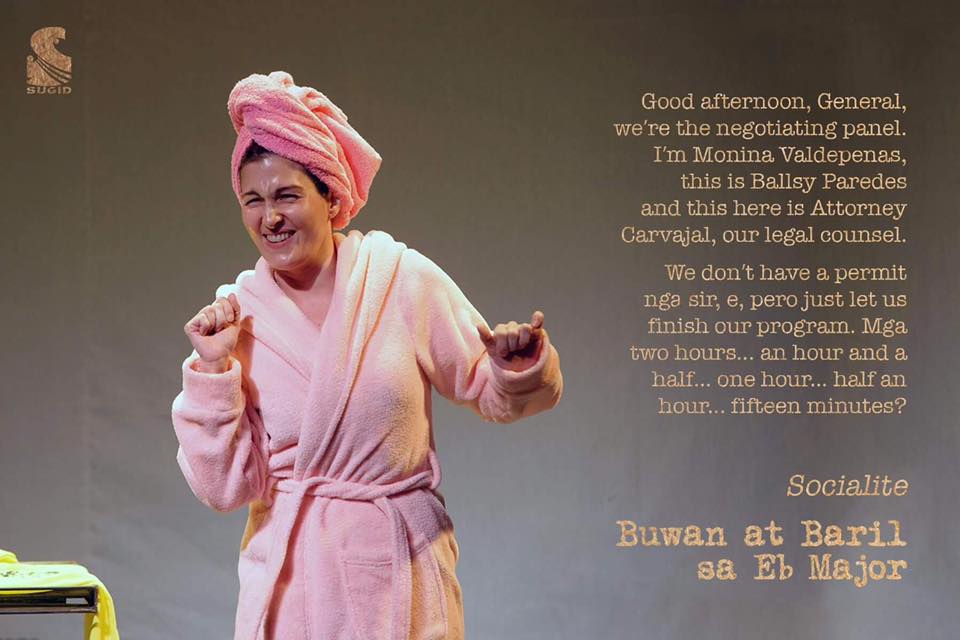

The Socialite’s (Jackie Lou Blanco) monologue of sharing her experience to her household help of social awakening and joining protests is a comic relief after the previous heavy acts. Blanco’s portrayal of the Socialite’s antics of how to negotiate in a protest she is about to attend and her conversations with her friends is quite hilarious. The act would make the audience realize that even the privileged can be encouraged to side with the cause of the people’s struggle once they are made to understand the actual situation of the oppressed masses. This was also most likely a homage to the participation of the upper middle class and richer sections in society leading to Edsa 1 in February 1986.

Cherry Pie Picache as the Asawa in the fourth story conveyed a message of a moment of confusion and doubt, but later on of resolve to claim the body of her slain rebel husband and pretend to be his cousin to protect her identity. Torn between continuing with her work as an activist in the city and giving up by shying away from the movement. As she comes closer home with her husband’s body, she realizes that she is not alone in the struggle and her son, even at a young age, understands somehow his parents’ cause and shows willingness to continue the fight.

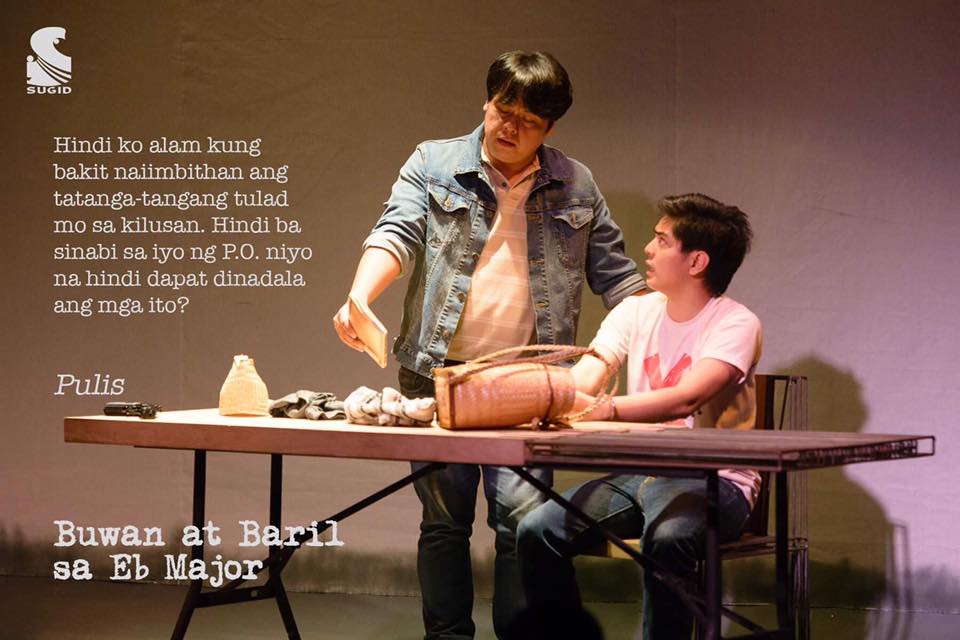

The last story was an interrogation and torture scene between the Pulis (Joel Saracho) and Estudyante (Ross Pesigan). The dialogue matched the tension-filled physical scenes with amusing and witty lines from both characters. The audience will be surprised with the Pulis’ background and would silently be relieved as the activist outwits the police as he pretended to be unknowledgeable and not deeply entrenched in the movement.

The use of live music with only a cello and an acoustic guitar is also commendable for its simplicity and gracefully tugged at the right emotions of the audiences in each story.

There were no elaborate props, stage design and choreography, and there was no need for them to make this play great. The combination of great talent and brilliant material was enough to come up with a well-crafted production and a masterpiece of theatre. Our country needs more cultural productions like this that not only focus on an individual’s struggle but also his/her connection to the society. There is a constant need to combat the prevailing culture of individualism haunting our youth, made to flourish more than ever in today’s social media.

But the play is not only stories of oppression and tragedy, but also stories of struggle and hope. And as we are confronted with the gloom of landlessness, increasing prices of commodities, everyday traffic, low wages, scuffled peace talks, extrajudicial killings, this is just about what we need to be staged in front of our eyes: a glint of hope that if we continue to struggle with the people, there is a better life, a better society ahead of us. As the last line “tulog na aking munting buwan” is solemnly delivered by the Asawa and all the characters lift their faces to watch the imaginary sleeping moon, we know that the sun is soon to rise, that light and hope amid the darkness would never fail to come.